Vison driven leadership

The School Leaders Register PO, the organization that represents the professional group 'school leaders in primary education' in the Netherlands, formulates the competence ' vision-oriented working' (one of the five established basic competences for school leaders) as follows:

“The school

leader leads the development and concretization of a joint vision on

education and propagates this vision in order to optimize educational

processes and learning results.”

Vision driven leadership: more than just creating support

Vision

driven leadership, however, is more than just creating support for a

certain policy course. It is also an important tool for stimulating the

intrinsic motivation of employees. And it is this intrinsic motivation

that in turn plays an important role in the development of creativity,

innovation and the willingness of employees to change and grow. All

aspects that are of great importance for today's organizations to cope

with an ever-changing environment.

Collective ambition

It is therefore becoming increasingly important for school leaders to consciously steer on the intrinsic motivation of their employees and the necessary mental models for this. One of the ways to actively shape this is to aim for a collective ambition (Weggeman, 2015). After all, according to Sinek (2011), the energy level and focus of professionals is a function of the ability to identify themselves with the values or higher goals of the organization. And it is these core values (shared values) that form the building blocks for the collective ambition.

Plan-Do-Check or Plan-Do-Trust?

A collective ambition ensures that employees can experience passion in their work, it inspires and gives meaning and direction. If the collective ambition in an organization is leading for the majority of employees, then according to Weggeman the well-known 'Plan-Do-Check-Action thing' can be thrown out and replaced by Plan-Do-Trust (Weggeman, 2015). By this he means that in the presence of a collective ambition, instead of planning and control, it is possible to work more from a culture of cooperation and trust. With the underlying basis of trust in each other's involvement and professional expertise.

Why vision driven leadership works

Vision driven leadership makes it possible to:

- to work on the basis of a shared sense of meaning;

- to work on realizing a shared ambition;

- to work on adaptive change;

If existing structures no longer offer a foothold, a strong sense of shared identity and belief in visions of the future can provide new footing!!!

There is therefore a relationship between the extent to which there is a collective ambition and the need for planning & control. The more there is a collective ambition, the smaller the need to 'manage' via planning & control becomes.

According to Blekkingh (2014), people with a vision have a clear motivation and a direction in which they want to go, because the creation drive is leading. If you have a strongly developed vision, this means, according to Blekkingh, that the vision is stored as a strong story in your inner world . A strong vision changes the perception of your environment. (For example, you will see opportunities that you otherwise would not see). Your filter becomes open to the data that are important for your vision. According to Blekkingh, it is conditional that you really believe in your vision. You have to be able to live through the vision, as it were, you have to be able to describe when you close your eyes what you see, hear, feel, possibly even smell and taste. You also need to be able to describe what your behavior is at that specific time in the future.As a leader, Blekkingh (2014) argues, it is a challenge to create a vision and to transfer it to others. If others adopt your vision, selective perception will make them more effective in a similar way. To achieve that, it is not enough to take them along in a presentation once or twice, you will have to be able to take the people along in their imagination to that future situation several times. (That's also the power of the scaling questions often used in coaching: what does it look like when it's 'an B-plus?) In other words, says Blekkingh, you have to come up with a way to anchor your vision as a strong story in the inner world of your people. Let them experience it as if it has already been realized. Examples: Martin Luther King speech (I have a dream that…. ) or making a newspaper dated in the future that contains all kinds of articles and advertisements that reflect the vision. Present your vision as if it were happening today. (Blekkingh, 2014).

Vision driven leadership fits in well with developments in the field of leadership, where a shift has occurred from transactional leadership – leading through rewards – to a more transformative form of leadership – leading by persuading and motivating employees to rise above their own interests and pursue the goals of the organization (Kelchtermans & Piot, 2010).

Incidentally, all kinds of variants have emerged on these two leadership styles, such as adaptive leadership . A leadership style that has been described by Heifetz in his book 'Leadership without easy answers' (Heifetz, 1994).

Other developments in theory development and research into (school) leadership focus in particular on distributed leadership. A theory that separates leadership from the person of the formal school leader (Brafman & Beckstrom, 2006; Kelchtermans & Piot, 2010; Spillane, 2005; Torrance, 2013).

Mission, vision and strategic policy

The mission-vision trajectory

The diagram below shows the process to arrive at a joint mission, vision and strategic policy. The most important concepts from this process and some relevant aspects are explained in more detail below.

Mission, vision and strategic policy

The concepts of mission and vision are used interchangeably in many policy documents or are always used as a pair of concepts (the mission and vision of the school are then described as a whole). In order to be able to work effectively with these concepts, it is important to keep the distinction between them clearly in mind. According to Kaplan & Norton (2008), mission is about what the organization now stands for. What you can recognize by now. If you allow your mission to be leading for a number of years, you will realize your vision (the dreamed-up image of the future). Your current vision then becomes, as it were, your new mission and further development of the vision takes place. The known dot on the horizon may therefore be reached, but a new dot is always being formulated (a new beckoning perspective), so that the organization continues to develop. In order to realize the vision, concrete goals that can be reached in time are derived from it and methods are provided to work on those goals (the strategic policy). The strategic policy therefore indicates the path that must be followed to realize the vision (Kaplan & Norton, 2008).

Vision or collective ambition?

Although both terms are sometimes used interchangeably, according to Mathieu Weggeman, a vision is much flatter. According to him, this is more about where an organization wants to be in three years' time, for example in terms of turnover level or market share. These are often quantitative goals, according to Weggeman. Collective ambition, according to Weggeman, is more qualitative, it is more philosophical. You ask yourself why you are there, what it would mean for the environment if the organization were no longer there. It is a search for the uniqueness of the organization: where is the sense of belonging, the esprit de corps, the family feeling? (Boer & Dikker, 2010).

Core values

Core values form the building blocks for the collective ambition (Weggeman, 2015). But where do those core values actually come from? Before we go further into this question, it is good to first make a distinction between personal core values and core values at an organizational level.

Core values, both personal and organizational, arise in a cyclical process, in which events are (selectively) observed and given meaning. The basic assumptions that arise from this then lead to the emergence of (core) values (Weick, 2005; Boonstra, 2011). This is shown schematically in the image below:

| |

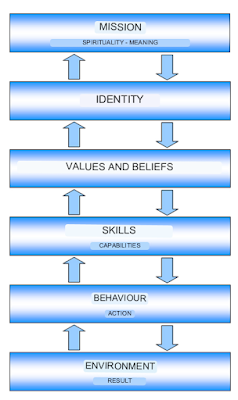

| Logical levels of Bateson, elaborated by Dilts (2014) |

Gregory Bateson's logical levels, further elaborated by Robert Dilts (2014) and depicted in the adjacent figure, describe a recursive ordering at the type level – and not at the content level (Tosey, 2006). This recursive order is sometimes compared to the well-known Russian matryoshka dolls that, if placed in the correct order, can be pushed together.Working with Bateson's logic levels

There are a few rules of thumb when working with Bateson's logic levels:

- Change at a lower level can bring about change at a higher level.

- Change at a higher level will effect change at all lower levels.

- The solution to a problem almost never lies at the level where the problem is found, but almost always at a different (higher) level.

When your skills and your behavior (in the environment you choose) are congruent with what you strive for at the highest levels, we speak of alignment. All levels then work together and support each other.

If your personal core values are not in line with those of the organization in which you work (environment), there is a good chance that sooner or later you will be expected to exhibit behavior that is not in line with your values and beliefs, or that you will be confronted with behavior from your environment that violates your core values. There is then no longer any question of alignment. You feel it wringing. If you are unable to align your core values and those of the organization (again), then sometimes there is nothing left but to leave the organization.

It should be noted that, according to Blekkingh (2014), most clashes between cultures can be traced not so much to a difference in values, but mostly to a difference in norms. So on how the values are expressed in rules and agreements.

Creating a collective meaning

A collective ambition ensures that employees can experience passion in their work, it inspires and gives meaning and direction (Weggeman, 2015). Processes of joint sense-making play an important role in the creation of a collective ambition (Wierdsma & Swieringa, 2011) and therefore also in vision-oriented working.

Kloosterboer (2012) also endorses the importance of shared meaning. In the form of observing and (re)valuing, it is therefore an important aspect of the cycle he describes as 'observing, appreciating, wanting and realizing'. He indicates that the use of so-called 'interpretation ladders' can help to gain more insight into each other's mental models.

|

| Interpretation ladder based on Kloosterboer (2012). |

The image on the left illustrates how the ladder works using a practical example: a colleague is late for an appointment. The example shows how this observation can lead to certain behavior in you.

The ladders also show that you can only climb into them from the bottom. Sideways, for example by convincing each other, the ladder is closed tight, according to Kloosterboer. That does not lead to agreement, but to stereotypes. For example, professional professionals sometimes look at managers (also professionals, by the way!) as annoying technocrats with a lack of professional knowledge. While managers see those professionals as headstrong and professionally deformed, with little regard for what is going on in the 'real world'. The result is talking past each other, arguing or withdrawing, the famous 'pocket veto'. Each remains locked in the rightness of his own ladder.

experiences and feelings that arise in this way, both the quality of the ladders of interpretation and the agreement between them increase. By entering into the process of perception and meaning together, you may therefore be able to prevent yourself from persuasion to arrive at a shared vision.

Sinek's Golden circle as a starting point

|

| Sinek's Golden circle (2011) |

You then end with the 'what question' (the product/result). In the example: 'If the child is more central, what do you see us doing or not doing? What organizational structures have been developed? What facilities are there then? etc.'

|

| Hedgehog Principle (Jim Collins, 2013) |

In order to properly formulate and propagate the educational vision, educational leadership is of great importance for the school leader. The school leader must also indicate and monitor the priorities. He can be guided by the Hedgehog Principle of Jim Collins (Collins, 2013).

Directional dilemmas

Choosing one also means consciously not choosing the other. As already stated, vision-oriented work means making choices and setting priorities. It is important to make these choices and their substantiation explicit in relation to the jointly formulated mission and vision.

Umbrella terms and professional orientations of teachers

In processes of joint sense-making, it is important to avoid getting stuck in umbrella terms, 'good language' and politically desirable answers by elaborating these further by jointly giving meaning and content to them. “Okay, we focus on 'the child', but what does that actually mean for us, what do you see us doing and what do you not see us doing?” This prevents people from going home after a study meeting, albeit satisfied, but with completely different images in their heads (and therefore also different expectations) with regard to the formulated vision and agreements made.

It is also advisable to keep in mind that teachers can differ greatly in their professional orientation (Veen, Sleegers, Bergen, & Klaassen, 2001). Based on a distinction in orientation on the method of instruction (knowledge transfer versus learning to learn), the goals of education (cognition and qualification versus a broader personal and moral education) and the attitude towards the school organization (autonomous and individualistic versus collaborative and participatory), Van Veen et al. distinguish six professional orientations. You can probably imagine that depending on the professional orientation, teachers can experience and color certain concepts differently emotionally. The joint explicitation (phrasing) and concretization (making concrete) of meanings with regard to generally formulated terms are used in the formulation of the mission and vision, with the consequence that in its practical elaboration everyone could shape them from their own interests and mental models.

Alignment

A well-known model for organizational development is Van Emst's wybertje (Loor, 2011). Central to this model is the importance of always paying attention to each side of the wybertje in an integrated manner during interventions.

Van Emst distinguishes:

- Strategic policy making : thinking systematically about a multi-year perspective for the school.

- The organizational structure : organization charts, tasks, powers, rules, etc.

- The systems : school information management system, registration of attendance, reporting system, system of study guides, et cetera. It is important to keep the energy that goes into the system side of an organization as low as possible. This is to prevent it from working against the professional culture.

- The professional culture : Van Emst distinguishes three types of culture: an official, a political and a professional culture. The professional culture describes the way in which the professionals in the school learn from each other.

|

| Wybertje from Van Emst. Taken from Loor (2011). |

Twisted organizations

|

| Working from the intention (Hart & Buiting, 2015). |

Formulating concrete and achievable goals in time

Once the mission and vision of the organization are known, it is possible to translate the vision into concrete goals that can be achieved in time and describe the working method used to achieve these goals. This is also referred to as formulating the strategic policy. One of the instruments that can be used is the Vision Deployment Matrix by Daniel Kim (1995).

Bibliography

Blekkingh, B. (2014). Authentiek leiderschap: Ontdek en leef je missie. Den Haag: Academic Service.

Boer, C. d., & Dikker, A. (2010, November 8). Hoogleraar Organisatiekunde Mathieu Weggeman weet raad. Retrieved Oktober 6, 2015, from Management Scope: http://managementscope.nl/magazine/artikel/516-interview-mathieu-weggeman#section_1

Boonstra, J. (2011). Leiders in cultuurverandering: Hoe Nederlandse organisaties succesvol hun cultuur veranderen en strategische vernieuwingen realiseren. Assen: Koninklijke Van Gorcum BV.

Brafman, O., & Beckstrom, R. (2006). The starfish and the spider. The unstoppable power of leaderless organizations. London: Penguin Books Ltd.

Collins, J. (2013). Good to Great. Amsterdam: Business Contact.

Dilts, R. (2014). Coachen vanuit een veelzijdig perspectief: from coach to awakener. Heemskerk: GV Media.

Hart, W., & Buiting, M. (2015). Verdraaide organisaties: terug naar de bedoeling. Alphen aan den Rijn: Vakmedianet Management B.V.

Heifetz, R. (1994). Leadership without easy answers. Cambridge Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Kelchtermans, G., & Piot, L. (2010). Schoolleiderschap aangekaart en in kaart gebracht. Leuven: Acco.

Kaplan, R., & Norton, D. (2008). Mastering the Management System. Harvard Business Review, 86(1), pp. 62 – 77.

Kim, D. (1995). Vision Deployment Matrix 1. Shifting from a reactive to a generative orientation. The Systems Thinker: A framework for large-scale change., 6(1).

Kim, D. (1995). Vision Deplyment Matrix 2: Crossing the chasm from reality to vision. The Systems Thinker: A framework for large scale change., 6(1).

Kloosterboer, P. (2012). Van Waarnemen naar Waarmaken: een expeditie naar Waarde met professionals. Den Haag: Academic Service.

Loor, O. d. (2011). Ontwikkelingsfasen van een nieuw school en passend leiderschap. Tijs, 5-17.

Sinek, S. (2011). Start with why. How great leaders inspire everyone to take action. London: Penguin Books Ltd.

Spillane, P. (2005). Distributed leadership. The Educational Forum, 143 – 150.

Torrance, D. (2013). Distributed leadership: challenging five generally held assumptions’. School Leadership and Management, 33(4), 354 – 372.

Tosey, P. (2006). Bateson’s Levels Of Learning: a framework for transformative learning? Universities’ Forum for Human Resource Development conference. (pp. 1-15). Tilburg: Universiteit van Tilburg.

Veen, K. v., Sleegers, P., Bergen, T., & Klaassen, C. (2001). Professional orientations of secondary school teachers towards their work. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17, 175 – 194.

Weggeman, M. (2015). Essenties van leidinggeven aan professionals. Hoe je door een stap terug te doen, beter vooruit komt. Schiedam: Scriptum management.

Weick, K., Sutcliffe, K., & Obstfeld, D. (2005). Organizing and the process of sensemaking. Organization Science, 16(4), 409-421.

Wierdsma, A., & Swieringa, J. (2011). Lerend organiseren en veranderen: Als meer van hetzelfde niet helpt. Groningen: Noordhoff Uitgevers.