Organizational culture

Origin of culture

Schein (1984) characterizes the concept of organizational culture as follows:

“Organizational culture is the pattern of basic assumptions that a given group has invented, discovered, or developed in learning to cope with its problems of external adaptation and internal integration, and that have worked well enough to be considered valid, and, therefore, to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think, and feel in relation to those problems.” (Schein, 1984)

According to Schein (1984) three levels can be distinguished with regard to the culture of an organization, which interact with each other (basic assumptions, values and artifacts & creations).

“Organizational

culture can be analyzed at several different levels, starting with the

visible artifacts — the constructed environment of the organization, its

architecture, technology, office layout, manner of dress, visible or

audible behavior patterns, and public documents such as charters,

employee orientation materials, stories. This level of analysis is

tricky because the data are easy to obtain but hard to interpret. We can

describe “how” a group constructs its environment and “what” behavior

patterns are discernible among the members, but we often cannot

understand the underlying logic — “why” a group behaves the way it

does.” (Schein, 1984)

Culture formation therefore arises when people gain experiences and then (jointly) indicate meaning. There is an important relationship here with co-creation, according to the cycle 'acting, contemplating, thinking, deciding and acting again' (Wierdsma & Swieringa, 2011) and with the cycle 'observing, (re)valuing, wanting and realizing' as described by Kloosterboer (2012).

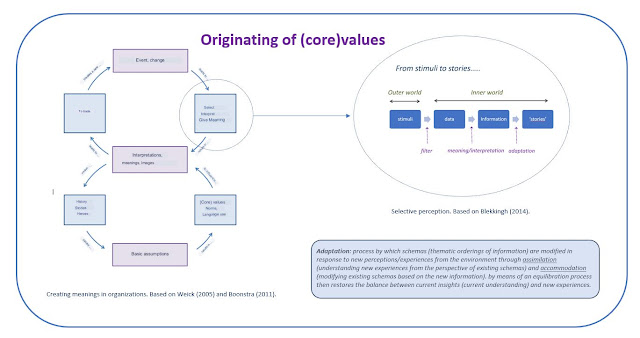

Core values play an important role in culture formation (Boonstra, 2011; Schein, 1984), they also form the building blocks of the collective ambition (Weggeman, 2015). But where do those core values actually come from? Core values, both personal and organizational, arise in a cyclical process, in which events are (selectively) observed and given meaning. The basic assumptions that arise from this then lead to the emergence of (core) values (Weick, 2005; Boonstra, 2011). For a summary of various core values, click here .

This is shown schematically as follows:

Triple loop learning

In cultural change processes it is important that learning takes place at three levels (Wierdsma and Swieringa, 2011). Triple loop learning is learning on three levels. In addition to the 'how' question (how can it be improved?) and the 'why' question (why did I do things the way I did? was the intention?).

In single-loop learning, knowledge and behavior are expanded by input from the environment. More profound change also requires 'meta-learning', or double loop learning, in which the frame of reference for the knowledge itself is revised. That frame of reference consists of the presuppositions, assumptions and attitudes on which our thinking and construction are based.

Through reflection we gain more insight into this frame of reference, which is usually only implicit, and we can step out of normal ways of thinking and become aware of our mental model. Triple loop learning means that reflection takes place on the level of action, the level of insights and the 'level of being'.

Triple loop learning is not only about the rules and procedures (single loop learning) and about the underlying insights and your beliefs (double-loop learning) but especially about your identity, your values and principles and your personal mission and vision. It therefore results not only in doing differently (improvement) but also in thinking differently (innovation) and 'being' different (presence, sustainable development).

Triple loop learning can also be related to McClelland's iceberg on a personal and organizational level. This is shown at organizational level in the image below. Taken from: Bergenhenegouwen & Mooijman (2010).

|

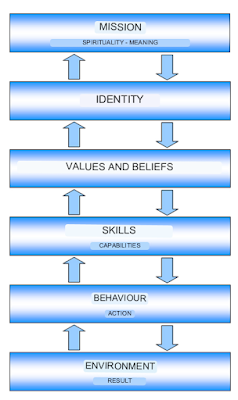

The Logical Levels of Gregory Bateson

| |

| Logical levels of Bateson, elaborated by Dilts (2014) |

Gregory Bateson's logical levels, further elaborated by Robert Dilts (2014) and depicted in the adjacent figure, describe a recursive ordering at the type level – and not at the content level (Tosey, 2006). This recursive order is sometimes compared to the well-known Russian matryoshka dolls that, if placed in the correct order, can be pushed together.

Working with Bateson's logic levels

There are a few rules of thumb when working with Bateson's logic levels:

- Change at a lower level can bring about change at a higher level.

- Change at a higher level will effect change at all lower levels.

- The solution to a problem almost never lies at the level where the problem is found, but almost always at a different (higher) level.

When your skills and your behavior (in the environment you choose) are congruent with what you strive for at the highest levels, we speak of alignment. All levels then work together and support each other.

If your personal core values are not in line with those of the organization in which you work (environment), there is a good chance that sooner or later you will be expected to exhibit behavior that is not in line with your values and beliefs, or that you will be confronted with behavior from your environment that violates your core values. There is then no longer any question of alignment. You feel it wringing. If you are unable to align your core values and those of the organization (again), then sometimes there is nothing left but to leave the organization.

It should be noted that, according to Blekkingh (2014), most clashes between cultures can be traced not so much to a difference in values, but mostly to a difference in norms. So on how the values are expressed in rules and agreements.

Normative and instrumental professionalism

With regard to the concept of professionalism, we can distinguish between normative professionalism (Smaling, 2005) and instrumental (technical) professionalism (Shulman, 1986). Normative professionalism includes professional behavior resulting from personal views and values (moral and attitude aspects). Instrumental professionalism is more about the knowledge and skills to be able to act instrumentally (technical aspects). The developed basic assumptions and core values of a person or organization therefore have a major influence on the development of normative professionalism.

Decision making processes

Good

decision making processes can make an important contribution to the

development of a professional culture (and vice versa). A

decision-making method that fits in very well with a professional

culture is meritocratic decision making (Hetebrij, 2011). This involves a

steering party that plans, organizes and supervises the decision making

process according to clear procedures. The participants in the

decision-making process are selected on the basis of a knowledge and

interest analysis. This ensures that the right people (with relevant

knowledge and good representation of the various stakeholders)

participate in the decision making process. In meritocratic

decision making, the rules are agreed in advance about the legitimacy of

exercising power (legitimization). This includes issues such as

(Hetebrij, 2011):

- Who gets to make a decision when?

- Will one person make the decision or a group?

- If a group: what is the voting procedure?

Levels of cooperation

1990_continuum collegiate relations - joint work_Little

Little (1990) has examined the mode of cooperation and degree of interdependence of teachers and placed it on a continuum. The highest attainable level that she distinguishes is 'joint work'. At this level of cooperation, teachers work together intensively in a Professional Learning Community like setting and are dependent on each other in order to achieve a (joint) result.

Levels of team development

Every team goes through different development phases. Within a team there is a growth process and a maturity level in which the team is. The most commonly used team development model is that of Tuckman (Nieuwenhuis, 2003-2010).

Development phases in a team according to Tuckman (1965). Source: Nieuwenhuis, M. (2003 -2010), The art of management. The-art.nl

Forming (Orientation phase) – There is no group feeling yet. Individual positions and roles have not yet been taken. Group members adopt a wait-and-see attitude and need direction.

Storming (Power Phase) – In this phase, the party members try to take their position in the group. This process often leads to strife when the ideas of the group members are at odds with each other.

Norming (Affection/Normization stage) – Group members get closer together. Rules and methods of cooperation are determined. The common team goals are shared and recorded. The emergence of a more task-mature way of working together.

Performing - There is now a team. Team members complement each other and work together harmoniously towards the common team goal. The team is able to work independently.

Adjourning (Farewell Phase) – The team is disbanded

The developmental stages of Tuckman (1965) are also linked to a certain maturity level of a team. At each maturity level certain characteristics and behavior of teams can be described (Nieuwenhuis, 2003-2010).

Analysis of the team culture

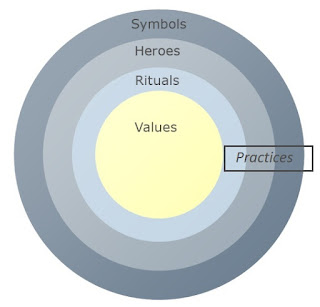

Onion model by Sanders and Neuijen (1987).

In this model, which mainly focuses on daily work practice and ingrained patterns, the organizational culture is presented as the rings of an onion. In this model, the core of a culture is formed by (core) values, often these values are implicitly present. The second ring (customs and rituals) concerns collective activities that have an independent meaning. These rituals lead to ingrained patterns of which people are hardly aware and which are often 'nourished' by people who act as role models ('heroes') in the organization – or who have acted in the past. Finally, the outer ring of the model contains the symbols and artifacts, such as logos, specific language, house style and all sorts of other external features.

As a (school) leader it is important to know the values, rituals, heroes and symbols of the organization well.

Competing values model according to Quinn (2008)

The basic idea behind this model is that attention should be paid to all quadrants of the model, tailored to the situation. The opposing quadrants in the model are based on opposite basic assumptions (and resulting opposite values). The trick now is to find the right balance between the four quadrants (and therefore between the different values). Hence the name 'competing values model'.

Based on Quinn's competing values model, the roles of the school leader in each quadrant can also be mapped. See image below.

Culture change

Culture is formed when people gain experiences and then develop new basic assumptions through a process of (joint) sense making. Through processes such as co-creation – according to the cycle 'acting, contemplating, thinking, deciding and acting again' (Wierdsma & Swieringa, 2011) – and the cycle 'observing, (re)valuing, wanting and realizing' as described by Kloosterboer (2012) can be directed at the cultural development within an organization. A great deal of attention should be paid to the quality of the processes of joint sense-making

“Learning together is not self-evident, it often takes effort and is sometimes very painful.” “It takes a lot of effort for learning organizations in general to keep learning.” (Wierdsma & Swieringa, 2011).

During co-creation, processes of shared meaning are constantly taking place. According to Wierdsma and Swieringa (2011), the quality of this can mainly be tested by looking at what people do when they are confronted with a multiple reality and a diversity of reactions to it, while, in order to get to work together, they have to make large need a clear meaning.

“The place of discomfort is the tension that arises in a situation that is ambivalent (dual value), while there is a desire to interpret it unambiguously.” (Wierdsma & Swieringa, 2011)

If a multiple reality has been interpreted unambiguously in a situation, an ordering result has been achieved. Reality has been given meaning. According to Wierdsma and Swieringa (2011), the shared meaning then forms the basis of collective action. Over time, however, it can be forgotten that the ordering result is the result of a negotiation process. It seems like it 'is' rather than 'made' that way. In such a situation, a process of reification (something is rightly or wrongly seen as an established fact) takes place. According to Wierdsma and Swieringa, people often make the plurality of a shared reality manageable by creating a meaning that enables them to coordinate their actions.

“Meanings do not exist, they cannot be discovered. Meanings are created.” (Wierdsma & Swieringa, 2011)

“Entering the place of discomfort is not just a matter of overcoming existing beliefs. People will have to learn to handle the relational dynamics and the emotions involved. Only then will an organization learn.” (Wierdsma & Swieringa, 2011)

According to Wierdsma and Swieringa (2011), the process of reification can be interrupted if people realize again that meanings are not objective realities, but are created. So they can change those meanings if they go back to the place of trouble, where the meanings were created. But then, they indicate, the tension must be accepted between the need for order and the still missing order result.

Homan (2014) speaks in this context of a cognitive monopoly that can arise in this context:

“If many tell (roughly) the same story, a cognitive monopoly arises: we can no longer think otherwise. The story is then no longer about reality, but will help shape that reality.” (Homan, 2014)

According to Wierdsma and Swieringa (2011), processes of discipline and exclusion constantly occur in interaction processes. Exclusion is the process by which people are no longer allowed to participate in the process of meaning creation. In addition to exclusion, processes of discipline often take place. People learn to think within the accepted frameworks and try to estimate what is socially desirable, in order to gain acceptance within the group (Wierdsma & Swieringa, 2011).

Sometimes there are processes in a group that can ensure that the place of trouble is not entered. Wierdsma and Swieringa (2011) mention, among other things, in this context:

Collective misjudgment: if people collectively act as if there are no development opportunities or if they believe that the organization is already learning.

Collective avoidance: if several people do not say what they really think or feel, this can lead to collective decisions or actions that (almost) none of the individuals want (Abilene paradox).

Collective ignorance: people are unable to deal constructively with internal differences. According to Wierdsma and Swieringa, it is then important to speak for yourself, to say exactly what you think or feel, by asking if you do not understand something and to paraphrase.

Collective unwillingness: for example, when people feel that the benefits of the ailment outweigh the benefits of the desired situation they are said to be striving for.

Selective perception

The quality of the meaning-making processes is also strongly influenced by the fact that people perceive selectively (Blekkingh, 2014). There is, as it were, a filter in our head that only lets through those stimuli that are considered important. This is also called selective perceptionor selective perception. This means that you have to be careful about the truthfulness of the perception of your environment. This restraint seems all the more important when you realize that this filtering largely takes place unconsciously. In addition, it is also the case that incentives that fit in well with the beliefs you already had are more likely to be passed than incentives that do not match your existing beliefs. This process is shown schematically in the image below.

Your brain uses this filter because otherwise it would not be able to process the overload of data. So the filter is a good mechanism in itself, but you should be aware of its limitations. You don't perceive a lot of things that are there (and vice versa, by the way).

The data that reach your inner world is converted into information. That is, meaning is given to it. So all kinds of 'stories' (meanings) are stored in your inner world, as it were. These stories are based on events that you once selectively observed and on the stories that you have developed yourself over the years. These stories represent your 'truth'.

“One story combines with another story to form a third story, etc. Stories about the skills and knowledge you have. Stories that shape your view of the world, about what is right and what is wrong and how you look at yourself.” (Blekkingh, 2014). It is therefore not for nothing that Wierdsma and Swieringa (2011) say “Meanings do not exist, they cannot be discovered. Meanings are created.”

Bibliography

Bergenhenegouwen, G., & Mooijman, E. (2010). Strategisch opleiden en leren in organisaties. Groningen/Houten: Noordhoff Uitgevers.

Blekkingh, B. (2014). Authentiek leiderschap: Ontdek en leef je missie. Den Haag: Academic Service.

Boonstra, J. (2011). Leiders in cultuurverandering: Hoe Nederlandse organisaties succesvol hun cultuur veranderen en strategische vernieuwingen realiseren. Assen: Koninklijke Van Gorcum BV.

Hetebrij, M. (2011). Een goed besluit is het halve werk. Van politieke spelletjes tot excellente besluitvorming. Assen: Van Gorcum.

Homan, T. (2014). Interactieperspectief op leiderschap. De Nieuwe Meso, 28 – 33.

Kloosterboer, P. (2012). Van Waarnemen naar Waarmaken: een expeditie naar Waarde met professionals. Den Haag: Academic Service.

Krüger, M. (2014). Leidinggeven aan onderzoekende scholen. Bussum: Coutinho.

Little, J. (1990). The persistence of privacy: Autonomy and initiative in teachers’ professional lives. Teachers College Record, 91(4), 509 – 536.

Nieuwenhuis, M. (2003 – 2010). The art of management. The-art.nl.

Quinn, R., Faerman, S., Thompson, M., McGrath, M., & St. Clair, L. (2008). Handboek Managementvaardigheden. Schoonhoven: Academic Service.

Rijst, R. v. (2009). The research-teaching nexus in the sciences: Scientific research dispositions and teaching practice. Proefschrift Leiden: ICLON.

Sanders, G., & Neuijen, B. (1987). Bedrijfscultuur. Diagnose en beïnvloeding. Uitgave Stichting Management Studies. Assen: Van Gorcum.

Schein, E. (1984). Coming to a new awareness of organizational culture. Sloan Management, 25(2), 3-16.

Shulman, L. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15, 4-14.

Smaling, A. (2005). Aspecten van normatieve professionaliteit in beroepssituaties. Tijdschrift voor Humanistiek, 6(22), 83-89.

Weick, K., Sutcliffe, K., & Obstfeld, D. (2005). Organizing and the process of sensemaking. Organization Science, 16(4), 409-421.

Wierdsma, A., & Swieringa, J. (2011). Lerend organiseren en veranderen: Als meer van hetzelfde niet helpt. Groningen: Noordhoff Uitgevers.